Learning from Disaster? After Sendai

After atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki there was in the West, especially the United States, a short triumphal moment, crediting American science and military prowess with bringing victory over Japan and the avoidance of what was anticipated at the time to be a long and bloody conquest of the Japanese homeland. This official narrative of the devastating attacks on these Japanese cities has been contested by numerous reputable historians who argued that Japan had conveyed its readiness to surrender well before the bombs had been dropped, that the U.S. Government needed to launch the attacks to demonstrate to the Soviet Union that it had this super-weapon at its disposal, and that the attacks would help establish American supremacy in the Pacific without any need to share power with Moscow. But whatever historical interpretation is believed, the horror and indecency of the attacks is beyond controversy. This use of atomic bombs against defenseless densely populated cities remains the greatest single act of state terror in human history, and had it been committed by the losers in World War II surely the perpetrators would have been held criminally accountable and the weaponry forever prohibited. But history gives the winners in big wars considerable latitude to shape the future according to their own wishes, sometimes for the better, often for the worse.

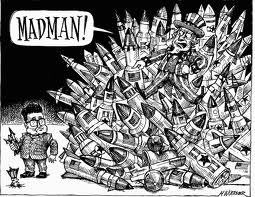

Not only were these two cities of little military significance devastated beyond recognition, but additionally, inhabitants in a wide surrounding area were exposed to lethal doses of radioactivity causing for decades death, disease, acute anxiety, and birth defects. Beyond this, it was clear that such a technology would change the face of war and power, and would either be eliminated from the planet or others than the United States would insist on possession of the weaponry, and in fact, the five permanent member of the UN Security Council became the first five states to develop and possess nuclear weapons, and in later years, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea have developed nuclear warheads of their own. As well, the technology was constantly improved at great cost, allowing long-distance delivery of nuclear warheads by guided missiles and payloads hundreds times greater than those primitive bombs used against Japan.

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki there were widespread expressions of concern about the future issued by political leaders and an array of moral authority figures. Statesmen in the West talked about the necessity of nuclear disarmament as the only alternative to a future war that would destroy industrial civilization. Scientists and others in society spoke in apocalyptic terms about the future. It was a mood of ‘utopia or else,’ and ‘on the beach,’ a sense that unless a new form of governance emerged rapidly there would be no way to avoid a catastrophic future for the human species and for the earth itself.

But what happened? The bellicose realists prevailed, warning of the distrust of ‘the other,’ insisting that it would be ‘better to be dead than red,’ and that nothing fundamental changed, that as in the past, only a balance of power could prevent war and catastrophe. The new name for balance in the nuclear age was ‘deterrence,’ and it evolved into an innovative, yet dangerous, semi-cooperative security posture that was given the formal doctrinal label of ‘mutual assured destruction.’ This reality was more popularly, and sanely, known by its expressive acronym, MAD, or sometimes this reality was identified as ‘a balance of terror,’ both a precursor of 9/11 language and a reminded that states have always been the supreme terrorist actors. The main form of learning that took place after the disasters of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was to normalize the weaponry, banish the memories, hope for the best, and try to prevent other states from acquiring it. The same realists, perhaps most prominently, John Mearsheimer, have even gone so far as to give their thanks to nuclear weaponry as ‘keepers of the peace’ during the Cold War. With some plausibility these nuclearists insisted that best explanation for why the Soviet Union-United States rivalry did not result in World War III was their shared fear of nuclear devastation. Such nuclear complacency was again in evidence when in the 1990s after the Soviet Union collapsed, there was a refusal to propose at that time the elimination of nuclear weaponry, and there were reliable reports that the U.S. Government actually used its diplomatic leverage to discourage any Russian disarmament initiatives that might expose the embarrassing extent of this post-deterrence, post-Cold War American attachment to nuclearism. This attachment has persisted, enjoys wide and deep bipartisan support in the United States, is shared with the leadership and citizenry of the other nuclear weapons states to varying degrees, and is joined at the hip to an anti-proliferation regime that hypocritically treats most states (Israel was a notable exception, and India a partial one) that aspire to have nuclear weapons of their own as criminal outlaws subject to military intervention. The counter-proliferation geopolitical regime has been superimposed upon the legal regime, and currently being used to threaten and coerce Iran in a manner that violates fundamental postulates of international law and the UN Charter.

Here is the lesson that applies to the present: the shock of the atomic attacks wears off in a few years, is unequivocally superseded by a restoration of normalcy surrounding the role of hard power whether nuclear or not. Because of evolving technology, this meant creating the conditions for repetition of the potential use of such weaponry at greater magnitudes of death and destruction. Such a pattern is accentuated, as here, if the subject-matter of disaster is clouded by the politics of the day that obscured the gross immorality and criminality of the historical use of the weapon, that ignored the fact that there are governmental forces associated with the military establishment that seek maximal hard power as an unconditional goal, and overlooked the extent to which these professional militarists are reinforced by paid cadres of scientists, defense intellectuals, and bureaucrats who build careers around the weaponry. This structure is, in turn, strongly reinforced in various ways by private sector profit-making opportunities, including a globally influential corporatized media. These conditions also apply with even less restraint across, undergirding the dirty business of international arms sales. At least with nuclear weapons the main political actors are much more prudent in their relations with one another than was the case in the pre-nuclear era of international relations, and have a shared and high priority incentive to keep the weaponry from falling into hostile hands.

We should also take account of the incredible ‘Faustian Bargain’ sold to the non-nuclear world: give up a nuclear weapons option and in exchange get an unlimited ‘pass’ to the ‘benefits’ of nuclear energy, and besides, the nuclear weapons states, while furtively winking to one another when negotiating the notorious Nonproliferation Treaty (1963) promised in good faith to pursue nuclear disarmament, and indeed general and complete disarmament. Of course, the bad half of the bargain has been fulfilled, although selectively, even in the face of the dire experiences of Three Mile Island (1979) and Chernobyl (1986), while the good half of the bargain (getting rid of the weaponry) never gave rise to even halfhearted nuclear disarmament proposals and negotiations (and instead the world settled irresponsibly for managerial fixes from time to time, negotiated arrangements known as ‘arms control’ measures that were designed to stabilize the nuclear rivalry of the U.S. and Soviet Union (now Russia) in mutually beneficial ways relating to financial burdens and risks. Such a contention has been recently confirmed by the presidential commitment to devote an additional $80 billion for the development of nuclear weapons before the U.S. Senate could be persuaded to ratify the New START Treaty in late 2010, the latest arms control ruse that was falsely promoted by Washington as a step toward disarmament and denuclearization. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with arms control, it may usefully reduce risks and costs under certain circumstances, but it is definitely not disarmament, and should not presented as if it is.

It is with this background in mind that the unfolding Japanese multidimensional mega-tragedy must be understood and its effects on future policy discussed in a preliminary manner. This extraordinary disaster originated in a natural event that was itself beyond human reckoning and control. An earthquake of unimaginable fury, measuring an unprecedented 9.0 on the Richter Scale, unleashing a deadly tsunami that reached a height of 30 feet, and swept inland in the Sendai area of northern Japan to an incredible distance up to 6 kilometers. It is still too early to count finally the number of the dead, the injured, the property damage, and the overall human costs, but we know enough by now to realize that the impact is already colossal, and will continue to grow, that this is a terrible happening that will be permanently seared into the collective imagination of humanity, perhaps the more so, because it is the most visually recorded epic occurrence in all of history, with real time video recordings of its catastrophic ‘moments of truth’ and sensationalist media reportage, especially via TV.

But this natural disaster that has been responsible for massive human suffering has been compounded by its nuclear dimension, the full measure of which remains uncertain at this point, although generating a deepening foreboding that is perhaps magnified by calming reassurances by the corporate managers of nuclear power in Japan (Tokyo Electric Power Company or TEPCO) who already had many blemishes on their safety record, as well as by political leaders, including Prime Minister Naoto Kan who understandably wants to avoid causing the Japanese public to shift from its impressive posture of traumatized, yet composed, witnessing to one of outright panic. There is also a lack of credibility based, especially, on a long record of false reassurances and cover ups by the Japanese nuclear industry, hiding and minimizing the effects of a 2007 earthquake in Japan, and actually lying about the extent of damage to a reactor at that time and on other occasions. What we need to understand is that the vulnerabilities of modern industrial society accentuate vulnerabilities that arise from extreme events in nature. There is no doubt that the huge earthquake/tsunami constellation of forces was responsible for great damage and societal distress, but the overall impact has been geometrically increased by this buying into the Faustian Bargain of nuclear energy, whose risks, if objectively assessed, were widely known for many years, yet effectively put to one side. It is the greedy profit-seekers, who minimize and suppress these risks, whether in the Gulf of Mexico or Fukushima or on Wall Street, and then scurry madly at the time of disaster to shift responsibilities to the victims that make me tremble as I contemplate the human future. These predatory forces are made more formidable because they have cajoled most politicians into complicity and have many allies in the media that overwhelm the publics of the world with steady doses of misinformation and tranquilizing promises of greater future care and protestations of societal need.

The reality of current nuclear dangers in Japan are far stronger than these words of reassurance that claim the risks to health are minimal because the radioactivity can even now be contained to avoid dangerous levels of contamination, although the latest reports indicate that already in nearby regions milk and spinach have tested as containing radiation above safe levels. A more trustworthy measure of the perceived rising dangers can be gathered from the continual official expansions of the evacuation zone around the six Fukushima Daiichi reactors from 3 km to 10 km, and more recently to 18 km, and more, coupled with the instructions to everyone caught in the region to stay indoors indefinitely, with windows and doors sealed. We can hope and pray that the four explosions that have so far taken place in the Fukushima Daiichi complex of reactors will not lead to further explosions or fires, and that a full meltdown in one or more of the reactors will not occur. Even without a meltdown the near certain venting of highly toxic radioactive steam to prevent unmanageable pressure from building up due to the boiling water in the reactor cores and spent fuel rods is likely to spread risks and harmful effects. It is a policy dilemma that has become a living nightmare: either allow the heat to rise and confront the high probability of reactor meltdowns or vent the steam and subject large numbers of persons in the vicinity and beyond to radioactivity, especially should the wind shift southwards carrying the steam toward Tokyo or westward toward northern Japan or Korea. In reactors 1, 2, and 3 are at risk of meltdowns, while with the shutdown reactors 4,5, and 6 pose the threat of fire releasing radioactive steam from the spent fuel rods.

We know that throughout Asia alone some 500 new reactors are either being built or have been planned and approved in the pre-Fukushima mood of energy worries, with as many as 150 destined for China alone. We know that nuclear power has been touted in the last several years as a major source of energy that is needed to deal with future energy requirements, a way of overcoming the challenge of ‘peak oil’ and of combating global warming by some decrease in carbon emissions. We know that the nuclear industry will contend that it knows how to build safe reactors in the future that will withstand even such ‘impossible’ events that have wrought such havoc in the Sendai region of Japan, while at the same time lobbying for insurance schemes to avoid such risks. Some critics of nuclear energy facilities in Japan and elsewhere had warned that these Fukushima reactors some built more than 40 years ago had become accident-prone and should no longer have been kept operational. Similar reactors are still operating around the world, including in the United States, with several near earthquake zones and close to large cities.And we know that governments will be under great pressure to renew the Faustian Bargain despite what should have been clear from the moment the bombs fell in 1945: This technology is far too unforgiving and lethal to be managed safely over time by human institutions, even if they were operated responsibly, which they are not. It is folly to persist, but it is foolhardy to expect the elites of the world to change course, despite this dramatic delivery of vivid reminders of human fallibility and culpability. We cannot hope to control the savageries of nature, although even these are being intensified by our refusal to take responsible steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but we can, if the will existed, learn to live within prudent limits even if this comes to mean a less materially abundant and an altered and less consumerist life style. The failure to take seriously the precautionary principle as a guide to social planning is a gathering dark cloud menacing all of our futures. Some specialists, including Amory Lovins and Jeremy Rifkin have argued that a blend of conservation, energy efficiency, and safe energy sources would satisfy the energy cravings of modern society without life style adjustments. Others, including Thomas Homer-Dixon, advocate the development of new major energy sources, in his case, deep geothermal drilling to tap into the heated core deep below the surface of the earth. [Globe and Mail, March 17, 2011, Canada]

Let us fervently hope that this Sendai disaster will not take further turns for the worse, but that the warnings already embedded in such happenings, will awaken enough people to the dangers on this path of hyper-modernity so that a politics of limits can arise to challenge the prevailing politics of limitless growth and consumerist profligacy. Such a challenge must include the repudiation of a neoliberal worldview, insisting without compromise on an economics and a human-centered vision of development based on needs and people rather than on profit margins, capital efficiency, and macro-economic indicators. Advocacy of such a course is admittedly a long shot, but so is the deadly collectivized utopian realism of staying on the nuclear course, whether it be with weapons or reactors. This is what Sendai should teach all of us! But will it?

III..15…2011 (updated III..20…2011)

Tags: Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, John Mearsheimer, New START, nuclear energy, nuclear reactors, Soviet Union, United States, World War II, World War III

A Modest Proposal: Is It Time for the Community of Non-Nuclear States to Revolt?

7 OctThere are 189 countries that are parties to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) that entered into force in 1970. Only India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea have remained outside the treaty regime so as to be free to acquire the weapons. The nuclear weapons states have done an incredibly successful job, especially the United States, in getting a free ride, continuously modernizing their arsenals while keeping the weapons out of most unwanted hands.

But the NPT was negotiated as a world order bargain. The non-nuclear countries would forego their weapons option in exchange for receiving the full benefits of nuclear energy and a pledge by the nuclear weapons states to seek nuclear disarmament in good faith. After 40 years it seems time to question both the benefits of nuclear energy (especially so after Fukushima) and even more the good faith of the members of the nuclear weapons club. Back in 1996 the World Court unanimously concluded that the nuclear weapons states needed to fulfill their treaty obligation to seek nuclear disarmament as a matter of urgency, and yet nothing resembling disarmament negotiations has taken place. It seems time to declare that the good faith obligation of Article VI of the treaty has been violated, and that this is a material breach that allows all states to disavow any obligation.

Two mind games have kept the non-nuclear majority of states in line so far: first, convincing the public that the greatest danger to the world comes from the countries that do not have the weapons rather than from those that do; secondly, confusing the public into believing that arms control measures are steps toward nuclear disarmament rather than being managerial steps periodically taken by the nuclear weapons states to cut the costs and risks associated with their weapons arsenals and programs and to fool the world into thinking they are living up to their obligation to phase out these infernal weapons of mass destruction.

There are other problems too. Israel has been allowed to acquire nuclear weapons by stealth without suffering any adverse consequences, while Iraq was invaded and occupied supposedly to dismantle their nuclear weapons program that turned out to be non-existent and Iran is under threat of military attack because its nuclear energy program has a built in weapons potential. Such double standards and geopolitical discrimination severely erode the legitimacy of the NPT approach.

Barack Obama earned much favorable publicity, and probably was given the Nobel Peace Prize, because in 2009 he made an inspirational speech in Prague announcing his commitment to a world without nuclear weapons. Although the speech was hedged with qualifications, including the mind-numbing reassurance to nuclearists not to worry, nothing would happen in Obama’s lifetime, it still gave rise to hopes that finally there would be a genuine attempt to rid the world of this nuclear curse. But it was not to be.

As with so many issues during the Obama presidency, the early gestures of promise were quietly abandoned in arenas of performance.

Has not the time come for the too patient 184+ non-nuclear weapons states to stand together with the peoples of the world to challenge the world nuclear weapons oligopoly? One way would be to declare the treaty null and void due to non-compliance by the nuclear weapons states. Such a move would be fully in accord with international treaty law.

Another way, perhaps more brash, but also maybe more likely to have a political impact, would be for as many non-nuclear states as possible to take a collective stand by way of an ultamatum: if the nuclear weapons states do not engage in credible nuclear disarmament negotiations designed to eliminate the weapons within two years, the treaty will be denounced.

Tags: Barack Obama, Iran, Israel, Nobel Peace Prize, North Korea, Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, Nuclear weapon, United States